Key takeaways

- MacroX sees the Chinese economy performing worse than official data suggests but there are no signs of a looming collapse

- Even with the surprise PBoC stimulus, activity has trended upwards only slightly in August

- Overindebted cities are responding slower to the stimulus.

- As authorities reduce the amount of official Chinese data, alternative data sources will be crucial.

We first published a post on the disappointing Chinese recovery in April. Since then, while the official data have turned lower, MacroX finds that the economic performance is worse than reported. Our alternative data and AI-based measure is in line with the unofficial Le Keqiang index. Below-trend activity in Australia, Brazil, and Taiwan – the main exporters to China provides additional support. In this post, we also discuss the lower response to stimulus of overindebted Chinese cities in less economically diverse and poorer provinces.

The official Chinese data have turned lower but no looming collapse

China’s Q2 GDP growth printed much weaker than Q1 (0.8% versus 2.2%) while exports (-14.5% yoy versus -12.5% consensus), industrial production (+3.7% yoy versus +4.4% consensus) and retail sales (+2.5% yoy versus +4.5% consensus) in July all disappointed relative to expectations. This weakness in demand has also caused Chinese prices to fall year-on-year in July, in sharp contrast to the inflation most of the world is experiencing.

Furthermore, China’s real estate market is in crisis as low housing demand has pushed real estate behemoths like Country Garden close to default and falling house prices have punctured consumer confidence. The relentlessness of the negative news has been overwhelming causing some news sources to look for a collapse. Our alternative data-based nowcast of economic activity shows the Chinese economy growing below trend but we see no signs of an imminent collapse.

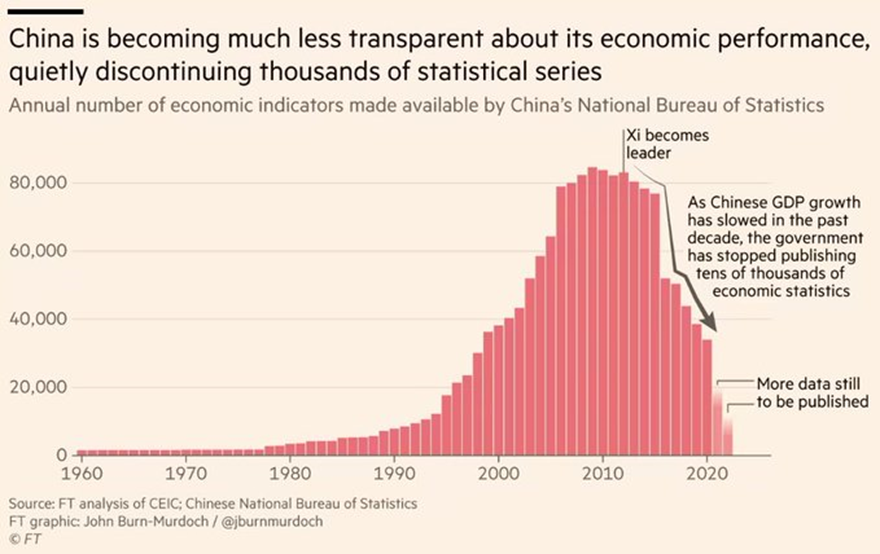

The case of disappearing official data

One of the consequences of the weak Chinese recovery has been a steady rise in youth unemployment which reached a record high of 21.3% in June. To the bemusement of China observers, the government suspended the release of this series last month citing measurement issues – the latest part of a disturbing trend of discontinuing thousands of statistical series that John Burn-Murdoch has reported on.

As granular official series disappear, it becomes harder to validate the headline indicators. Luckily, the ocean of alternative data generated due to technological advances provides alternative ways of observing the Chinese economy.

Alternative Data provide a new way of measuring economic activity

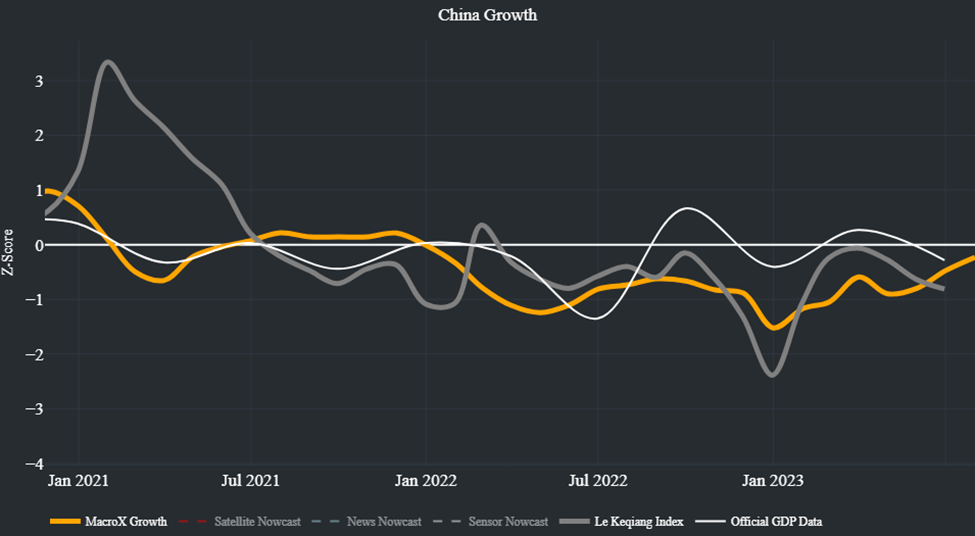

At MacroX, we feed 100+ alternative data sources into our AI engine to measure Chinese output in real-time. Our headline measure shows Chinese activity trending upwards in August but from low levels:

As Figure 2 shows, our measure of Chinese economic activity shows growth below the official government data thus far in 2023, with an uptick in August. Our measure (gold) is more in line with the well-known Le Keqiang Index (grey) and lower than the official data (white).

To gain a more granular understanding of what’s driving this move upwards, we can dive into the components of our Nowcast.

· Satellite nowcast (red) shows that manufacturing activity is low but rising

· Sensor nowcast (white) shows overall activity levels including services to be a bit higher

· News nowcast (blue) show low macroeconomic sentiment in the Chinese media

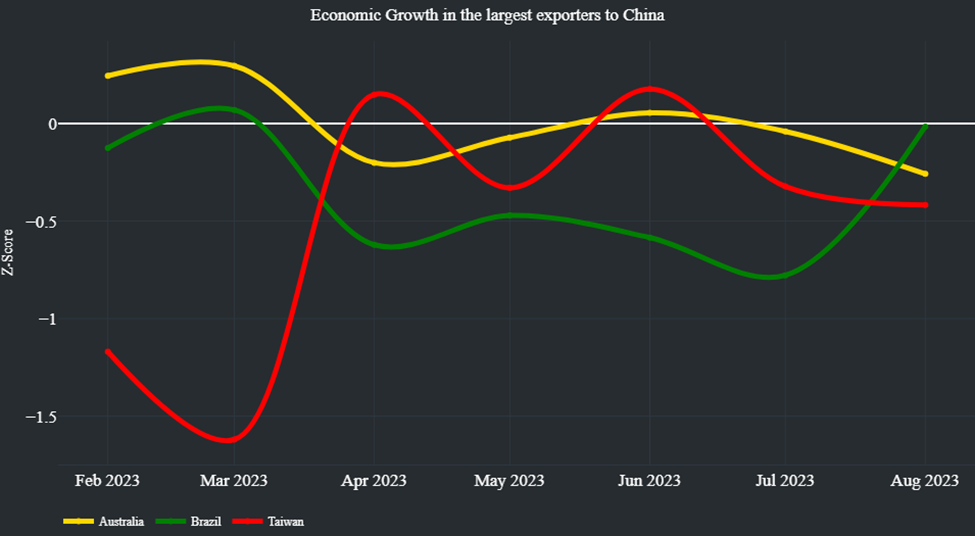

Performance of major trading partners

Further validation of the weakness in Chinese performance can be seen by looking at the economic performance of the biggest exporters to China. Taiwan, Australia, and Brazil had the highest trade surpluses in 2022 versus China and our nowcasts show below-trend growth in all three in 2023.

Regional differences

Scholars such as Michael Pettis have argued about the unsustainability of unbalanced growth in China. He notes that the economy is splitting into two tiers – one of wealthier, economically diverse provinces and others dependent on debt-fueled growth. Given the easing of monetary policy has been the key policy lever pulled by authorities so far, one would expect this to be less effective for provinces with high debt levels.

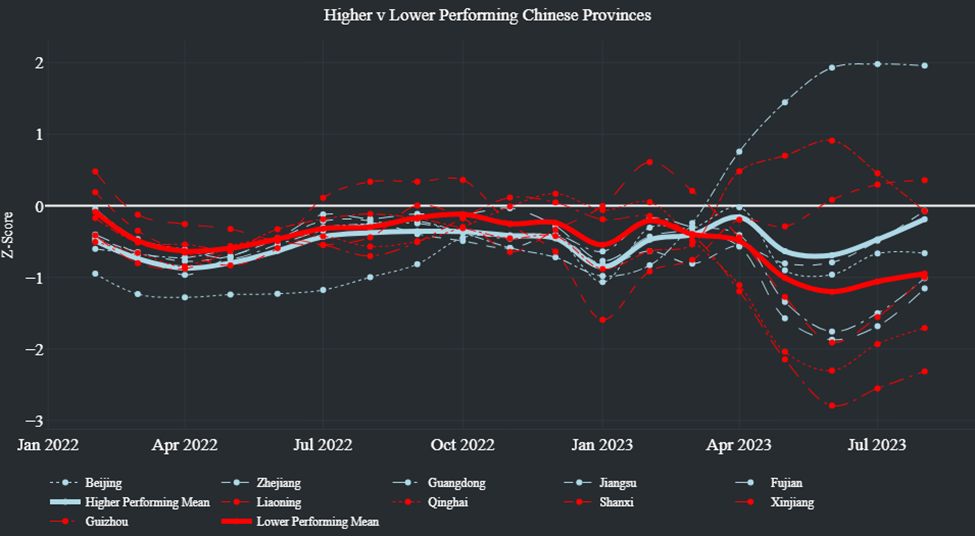

To assess this, using city-level data for over 80 cities from our nowcasting engine, we construct regional portfolios of the five highest-ranked provinces (Guangdong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Beijing) versus the five lowest (Liaoning, Qinghai, Shanxi, Xinjiang, Guizhou) according to Alexander Campbell.

We can see that economic performance across the two city portfolios was broadly similar in 2022 (as the country was still in the grips of its zero-covid policy). However, since the start of 2023, there has been a sharp divergence in economic performance. Interestingly, growth fell much more sharply in the lower-performing portfolio in Q2 2023 while growth has moved much more sharply upwards in the higher-performing portfolio in Q3, giving credence to Pettis’ view of a two-tier China.

In particular, our city-level nowcasts show that economic activity in Jiangsu has been particularly robust this year, adding credence to the official data provided by the province’s statistical bureau suggesting that growth was 6.2% yoy at the end of H1 2023.

Stimulus is coming but what effect will it have?

The downward turn in economic data has lead to the PBoC lowering the rate on its one-year loans twice – the latest 15bp cut occurring on 08/21 –demonstrating that Chinese economic authorities are well aware of the malaise the country’s economy is gripped by. Further measures are likely, although seasoned China observers are insistent that measures to boost consumption will be integral for China to achieve a balanced growth path. Whatever Beijing decides to do, MacroX will be the first to see the effects of any new stimulus measures on the economy demonstrating the power of using real-time alternative data.